1. (bonda, by)

Wæs ðu hal! Ic hatte Wulfstan.

Hello, my name is Wulfstan.

Wes þú haill! Ek haiti Gunnhildr.

Hello, my name is Gunnhildr

Min fæder is bonda. Ðis is his land, his croft. He ah feower cy and seox sceap.

My father is a farmer. This is his land, his farm. He has four cows and eight sheep.

Faðir mín ok es bóndi. Bú hans es þar. Hann á fjórir kýr ok sex sauðr.

My father is also a farmer. His farm is over there. He also has four cows and eight sheep.

2. (knife, take, mun)

Min fæder hæfð me beden miceles cnif. He þearf manige rapas sceran.

My father has asked me for a big knife. He needs to cut ropes.

Faðir mín hefir beðit mik knífs lítils. Hann þarf epli skera.

My father has asked me for a small knife. He needs to cut apples.

Ðær is lytel cnif. Nim hit!

There is a small knif there. Take it!

Já, ek þanka þér. Ek mun taka þann.

Yes, thank you. I will take it.

3. (leg, kid )

Lít! Leggr kiðins es sárr.

Look! The kid’s leg is sore.

Hwær?

Where?

Þar! Við tréit!

There! By the tree!

Be treowe? Hwæt is kið? Ic cann seon ænlice ticcen. His scanca is sceþed.

By the tree? What is a kid? I can only see a ‘kid’. His leg is cut. —

1. Listen to these dialogues between Gunnhildr, a ten-year-old girl born to Scandinavian parents from a farm nearby in Yorkshire (she speaks in Old Norse), and Wulfstan, a nine-year-old English boy (he speaks in Old English).

a. Let’s think first about the words that were very similar in Old English and Old Norse. Here are some Old English words. Can you find the equivalent terms in Old Norse? [click and Norse cognates appear}

feower ‘four’. [ON fjórir]

seox ‘six’ [ON sex]

cu ‘cow’ (plural cy) [ON kú/ kýr]

fæder ‘father’ [ON faðir]

lytel ‘little, small’ [ON lítill]

sceran ‘to shear, cut’ [ON skera]

æppel ‘apple’ (pl. æppla) [ON epli]

ic ‘I’ [ON ek]

treow ‘tree’ [ON tré – notice how Old Norse puts the definite article -it ‘the’ on the end of the word]

hæfð beden ‘has asked’ [ON hefir beðit]

sar ‘sore’ [ON sárr]

b. Wulfstan and Gunnhildr can understand each other because most of their words are very similar. Some words are different between the two languages though. Can you spot any instances where Wulfstan and Gunnhildr use different words for the same thing? [click to reveal]

farm Wulfstan describes a farm using the words land and croft, but the word Gunnhildr uses is bú. The word farm came to be used in the modern sense under the influence of Anglo-Norman French.

kid Gunnhildr uses the word kið, but the Old English word for a baby goat that Wulfstan knows is ticcen.

take The usual verb meaning ‘take’ in Old English, which Wulfstand uses, was niman. The word Gunnhildr knows is Old Norse taka.

Notice that in some of these cases it is the Old Norse word that looks more familiar from modern English.

The similarity of the two languages is easier to spot when you listen to the dialogues spoken than when you read them, because the same sounds are sometimes spelt differently according to modern conventions. For example, the accent on Old Norse sárr simply indicates a long vowel.

You will notice that many of the words are the same, or sound very similar. An English speaker would have had no trouble recognizing the word tré. Old Norse tré would have sounded like some variants of the native English word in the Middle English period. This may be why these variant were more popular in Northern Middle English and why ultimately tree became the standard Modern English word.

This close relationship between the languages is because descend come from a common source, which we call Proto-Germanic. Proto-Germanic is older than any written records, but we can tell what it must have sounded like by comparing the languages that descent from it, which also include languages like German and Dutch. [image of family tree].

The medieval forms of these languages had not changed as much as their modern descendants, and speakers would have found it much easier to understand each other than modern speakers of English and Norwegian or Swedish and Dutch do. The greater similarity however, makes it harder for us to identify which words originally come from which languages.

Most of our words are already recorded in Old English. Some only appear for the first time in Middle English. There are two ways of explaining this:

- The word was already there in Old English, but didn’t happen to be written down in any surviving text. This is a better explanation for a word that might have been used more rarely, or wouldn’t have been considered appropriate for the kinds of literary texts that were written down in manuscripts.

- The word was not present in Old English, but was borrowed into English from another language, such as Old French or Old Norse. This is the more likely explanation if the word is very common, like take (borrowed from Old Norse taka). Old English already had words to express such a basic concept.

French words are easy to spot on the whole. French is a Romance language more distantly related to the Germanic family. Old Norse words are more difficult to spot because they can sound so much like English words.

b. Are you ready to try and spot Norse-derived words in English? Listen/read the dialogues again, focus on the words spoken by Ulfketill and try to identify 7 words that English has borrowed from Old Norse. When you are ready to check your answers, press here. [bonda, by, knife, take, mun, leg, kid]

The word bonda, which Wulfhild uses to mean farmer is originally from Old Norse (compare Ulfketill’s word, bóndi). We can see that it was already in use in Old English because it is recorded in early texts. This is also the case with knife, which both children also understand. Other words from Old Norse are only recorded in English later, however. Wulfhild does not recognize the words leg and kid, for example.

If the Vikings had been in England since the end of the 8th century, why do some of their words only appear in English so much later? There are two important factors to consider here. One is where the Vikings were and where Old English texts comes from. Most surviving Old English texts come from areas in the south, which were least impacted by contact with Scandinavians. Few people would have been able to read and write, moreover, and those that did were careful to stick to what they would have considered ‘proper’ English.

The second factor we have to consider is how Old Norse words came into the language. As Scandinavian families like Ulfketill’s settled on farms in England and lived side by side with their English-speaking neighbors for years, they would have gradually switched over to speaking English themselves. This meant using some of their Old Norse words in English – which as we have seen would have been easy to without causing real difficulties in understanding. Even their pronunciation of English words would have been influenced by similar words in Old Norse. A common example is the ‘g’ sound at the beginning of the verbs give and get. These words were very similar in Old English (giefan, gifan and -gietan, -getan), but there they were pronounced with a ‘y’ sound.

Even though we do not have records from the Viking age of many dialects like the one imagined here, we can reconstruct what they must have been like by looking at all the English words, right down to the present day, that show signs of Old Norse influence.

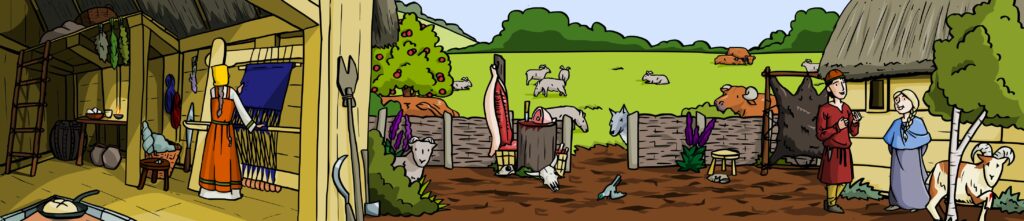

2. Many everyday objects have names that derive from Old Norse. See if you can find these examples in this farm scene: 1 cake, 2 skulls (there is an area with some carcasses), bear skin, 3 eggs, working gear (i.e. some basic tools to work the land), 2 seats, 1 window, a bird with only one wing, 2 plants in full bloom, 1 sly wolf, 1 odd shoe, 1 skilful weaver, 1 loft 2b. game 2

Wes hal!

Hello

Wes haill!

Hello

Hwa eart þu?

Who are you?

Ek haiti Gunnhildr. Hwerr estu?

I am called Gunnhildr. Who are you?

Ic hatte Wulfstan. Is þat scip?

I am called Wulfstan. Is that a ship?

Nei, þat es skip. Ok þessi es fiskr.

No, it is a ship. And this is a fish.

Ic wat! Fiskr is fisc.

I know! Fiskr is fish.

Ek vait, fisk.

I know, fish.

Wyrcest þu þat scip?

Did you make the ship?

Nei, móðir mín.

No, my mother [did].

Min modor siwode þas scyrte.

My mother sewed this shirt.

Sú es skyrta.

That is a skirt.

Wilt þu beon freond min?

Will you be my friend?

Ja, Ek wil wesa frændr þín.

Yes, I will be your friend.

1. Which word sound different in Old English and Old Norse? Can you spot any sounds in Old English that regularly correspond to a different sound in Old Norse?

1b. What other English words can you think of with an ‘sk’ sound that might come from Old Norse?

Here are just a few: skull, skill, sky, skirt, scathe, scare, scale and skin

1c. Game 1

2. Many features of the landscape, particularly in Northern England, have Old Norse names. Can you spot some in this picture? [click to reveal]

Bank/banke

The Old Norse word is related to the English word ‘bench’.

Dale/dalr

This word is most common in the North and Northeast of England, an area with strong Scandinavian influence.

Fell/fjall, fell

Gill/gil

There are many place-names in Northwest England that include this term, such as Blagill in Cumbria.

Carr/kjarr

A carr refers to wet, boggy ground.

Do you know any places with names that use these words?